Abstract

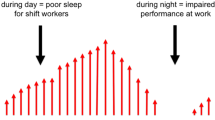

Almost 15% of the full-time workers in the United States are shift workers. We review the physiologic challenges inherent not only in traditional night or rotating shifts but also in extended-duration shifts and other nonstandard hours. The challenging schedules of those in particularly safety-sensitive professions such as police officers, firefighters, and health care providers are highlighted. Recent findings describing the neurobehavioral, health, and safety outcomes associated with shift work also are reviewed. Comprehensive fatigue management programs that include education, screening for common sleep disorders, and appropriate interventions need to be developed to minimize these negative consequences associated with shift work.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Bureau of Labor Statistics: Workers on Flexible and Shift Schedules in May 2004. Available at http://www.bls. gov/news.release/pdf/flex.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2009.

Folkard S, Lombardi DA: Modeling the impact of the components of long work hours on injuries and “accidents.” Am J Ind Med 2006, 49:953–963.

Dijk DJ, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA: Circadian and sleep/wake dependent aspects of subjective alertness and cognitive performance. J Sleep Res 1992, 1:112–117.

Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA: Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, sleep structure, electroencephalographic slow waves, and sleep spindle activity in humans. J Neurosci 1995, 15:3526–3538.

Folkard S, Tucker P: Shift work, safety and productivity. Occup Med (Lond) 2003, 53:95–101.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Traffic Safety Facts 1999: A Compilation of Motor Vehicle Crash Data From the Fatality Analysis Reporting System and the General Estimates System. Washington, DC: National Center for Statistics and Analysis; US Department of Transportation; 2000.

Department of Transportation: Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. Fed Reg 2000, 65(85):25541–25611.

Dawson D, Reid K: Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature 1997, 388:235.

Lamond N, Dawson D: Quantifying the performance impairment associated with fatigue. J Sleep Res 1999, 8:255–262.

Hack MA, Choi SJ, Vijayapalan P, et al.: Comparison of the effects of sleep deprivation, alcohol and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) on simulated steering performance. Respir Med 2001, 95:594–601.

Balkin T, Rupp T, Picchioni D, Wesensten N: Sleep loss and sleepiness: current issues. Chest 2008, 134:653–660.

Van Dongen HP, Maislin G, Mullington JM, Dinges DF: The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: doseresponse effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep 2003, 26:117–126.

Belenky G, Wesensten NJ, Thorne DR, et al.: Patterns of performance degradation and restoration during sleep restriction and subsequent recovery: a sleep dose-response study. J Sleep Res 2003, 12:1–12.

Dinges DF: Are you awake? Cognitive performance and reverie during the hypnopompic state. In Sleep and Cognition. Edited by Bootzin R, Kihlstrom J, Schacter D. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1990:159–175.

Achermann P, Werth E, Dijk DJ, Borbély AA: Time course of sleep inertia after nighttime and daytime sleep episodes. Arch Ital Biol 1995, 134:109–119.

Dinges DF: Sleep inertia. In Encyclopedia of Sleep and Dreaming. Edited by Carskadon MA. New York: Macmillan Publishing; 1993:553–554.

Wertz AT, Ronda JM, Czeisler CA, Wright KP Jr.: Effects of sleep inertia on cognition. JAMA 2006, 295:163–164.

Jewett ME, Wyatt JK, Ritz-De Cecco A, et al.: Time course of sleep inertia dissipation in human performance and alertness. J Sleep Res 1999, 8:1–8.

Scheer FA, Shea TJ, Hilton MF, Shea SA: An endogenous circadian rhythm in sleep inertia results in greatest cognitive impairment upon awakening during the biological night. J Biol Rhythms 2008, 23:353–361.

Silva EJ, Duffy JF: Sleep inertia varies with circadian phase and sleep stage in older adults. Behav Neurosci 2008, 122:928–935.

Ribak J, Ashkenazi IE, Klepfish A, et al.: Diurnal rhythmicity and air force flight accidents due to pilot error. Aviat Space Environ Med 1983, 54:1096–1099.

Di Lorenzo L, De Pergola G, Zocchetti C, et al.: Effect of shift work on body mass index: results of a study performed in 319 glucose-tolerant men working in a Southern Italian industry. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003, 27:1353–1358.

Knutsson A: Health disorders of shift workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2003, 53:103–108.

Davis S, Mirick DK, Stevens RG: Night shift work, light at night, and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001, 93:1557–1562.

Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, et al.: Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol 2007, 8:1065–1066.

Davis S, Mirick DK: Circadian disruption, shift work and the risk of cancer: a summary of the evidence and studies in Seattle. Cancer Causes Control 2006, 17:539–545.

Guilleminault C, Czeisler C, Coleman R, Miles L: Circadian rhythm disturbances and sleep disorders in shift workers. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl 1982, 36:709–714.

Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Ten Have T, et al.: Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998, 157:144–148.

Leger D: The cost of sleep-related accidents: a report for the National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research. Sleep 1994, 17:84–93.

Findley LJ, Unverzagt ME, Suratt PM: Automobile accidents involving patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988, 138:337–340.

Sassani A, Findley LJ, Kryger M, et al.: Reducing motor-vehicle collisions, costs, and fatalities by treating obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 2004, 27:453–458.

Krieger J, Meslier N, Lebrun T, et al.: Accidents in obstructive sleep apnea patients treated with nasal continuous positive airway pressure: a prospective study. The Working Group ANTADIR, Paris and CRESGE, Lille, France. Association Nationale de Traitement a Domicile des Insuffisants Respiratoires. Chest 1997, 112:1561–1566.

Aldrich MS: Automobile accidents in patients with sleep disorders. Sleep 1989, 12:487–494.

Vila B: Impact of long work hours on police officers and the communities they serve. Am J Ind Med 2006, 49:972–980.

The National Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program (Federal Bureau of Investigation): Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted; 2004. Available at http://www. fbi.gov/ucr/killed/2004/openpage.htm. Accessed January 29, 2009.

Vila B, Kenney DJ: Tired cops: the prevalance and potential consequences of police fatigue. NIJ J 2002, 248:16–21.

Neylan T, Metzler M, Best S, et al.: Critical incident exposure and sleep quality in police officers. Psychosom Med 2002, 64:352.

Garbarino S, Nobili L, Beelke M, et al.: Sleep disorders and daytime sleepiness in state police shiftworkers. Arch Environ Health 2002, 57:167–173.

Rajaratnam SMW, Barger LK, Lockley SW, et al.: Screening for sleep disorders in North American police officers [abstract]. Sleep 2007, 30(Suppl):A209.

Violanti JM, Vena J, Marshall JR, Petralia S: A comparative evaluation of police officer suicide rate validity. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1996, 26:79–85.

Violanti JM, Vena J, Petralia S: Mortality of a police cohort: 1950-1990. Am J Ind Med 1998, 33:366–373.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Fatalities among volunteer and career firefighters—United States, 1994–2004. JAMA 2006, 295:2594–2596.

Elliott D, Kuehl K: Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Fire Fighters and EMS Responders. Fairfax, VA: International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) and the United States Fire Administration (USFA); 2007.

Murphy S, Beaton R, Cain K, Pike K: Gender differences in fire figher job stressors and symptoms of stress. Women Health 1994, 22:55–69.

Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, et al.: Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med 2005, 352:125–134.

Ayas NT, Barger LK, Cade BE, et al.: Extended work duration and the risk of self-reported percutaneous injuries in interns. JAMA 2006, 296:1055–1062.

Barger LK, Ayas NT, Cade BE, et al.: Impact of extendedduration shifts on medical errors, adverse events, and attentional failures. PLoS Med 2006, 3:0001–0009.

Arnedt JT, Owens J, Crouch M, et al.: Neurobehavioral performance of residents after heavy night call vs after alcohol ingestion. JAMA 2005, 294:1025–1033.

Philibert I: Sleep loss and performance in residents and nonphysicians: a meta-analytic examination. Sleep 2005, 28:1392–1402.

Rogers AE, Hwang WT, Scott LD, et al.: The working hours of hospital staff nurses and patient safety. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004, 23:202–212.

Scott LD, Rogers AE, Hwang WT, Zhang Y: Effects of critical care nurses’ work hours on vigilance and patients’ safety. Am J Crit Care 2006, 15:30–37.

Trinkoff AM, Le R, Geiger-Brown J, Lipscomb J: Work schedule, needle use, and needlestick injuries among registered nurses. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007, 28:156–164.

Czeisler CA, Moore-Ede MC, Coleman RM: Rotating shift work schedules that disrupt sleep are improved by applying circadian principles. Science 1982, 217:460–463.

Lockley SW, Cronin JW, Evans EE, et al.: Effect of reducing interns’ weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failures. N Engl J Med 2004, 351:1829–1837.

Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, et al.: Effect of reducing interns’ work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med 2004, 351:1838–1848.

Eastman CI, Boulos Z, Terman M, et al.: Light treatment for sleep disorders: consensus report. VI. Shift work. J Biol Rhythms 1995, 10:157–164.

Hanifin JP, Brainard GC: Photoreception for circadian, neuroendocrine and neurobehavioral regulation. J Physiol Anthropol 2007, 26:87–94.

Sharkey KM, Eastman CI: Melatonin phase shifts human circadian rhythms in a placebo-controlled simulated nightwork study. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2002, 282:R454–R463.

Walsh JK, Muehlbach MJ, Humm TM, et al.: Effect of caffeine on physiological sleep tendency and ability to sustain wakefulness at night. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990, 101:271–273.

Wyatt JK, Cajochen C, Ritz-De Cecco A, et al.: Low-dose, repeated caffeine administration for circadian-phasedependent performance degradation during extended wakefulness. Sleep 2004, 27:374–381.

Czeisler CA, Walsh JK, Roth T, et al.: Modafinil for excessive sleepiness associated with shift work sleep disorder. N Engl J Med 2005, 353:476–486.

Rosa RR, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, et al.: Intervention factors for promoting adjustment to nightwork and shiftwork. Occup Med 1990, 5:391–415.

Neri DF, Mallis MM, Oyung RL, Dinges DF: Do activity breaks reduce sleepiness in pilots during a night flight. Sleep 1999, 22:s150.

Lockley SW, Evans EE, Scheer FA, et al.: Short-wavelength sensitivity for the direct effects of light on alertness, vigilance, and the waking electroencephalogram in humans. Sleep 2006, 29:161–168.

Porcu S, Bellatreccia A, Ferrara M, Casagrande M: Performance, ability to stay awake, and tendency to fall asleep during the night after a diurnal sleep with temazepam or placebo. Sleep 1997, 20:535–541.

Arendt J, Rajaratnam SM: Melatonin and its agonists: an update. Br J Psychiatry 2008, 193:267–269.

Rosekind MR, Graeber RC, Dinges DF, et al.: Crew Factors in Flight Operations IX: Effects of Planned Cockpit Rest on Crew Performance and Alertness in Long-Haul Operations [technical memo 108839, 1–64]. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 1994.

Santhi N, Horowitz TS, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA: Acute sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment associated with transition onto the first night of work impairs visual selective attention. PLos ONE 2007, 2:e123.

Van Dongen HPA, Baynard MD, Maislin G, Dinges DF: Systematic interindividual differences in neurobehavioral impairment from sleep loss: evidence of trait-like differential vulnerability. Sleep 2004, 27:423–433.

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, edn 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Sullivan JJ: Fighting fatigue. Public Roads. Available at http://www.tfhrc.gov/pubrds/03sep/04.htm. Accessed January 29, 2009.

FIT 2000; Fitness-for-Duty/Impairment Screeners. Available at http://www.pmifit.com/. Accessed Feburary 5, 2009.

Cajochen C, Khalsa SBS, Wyatt JK, et al.: EEG and ocular correlates of circadian melatonin phase and human performance decrements during sleep loss. Am J Physiol 1999, 277:R640–R649.

Jewett ME, Dijk DJ, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA: Sigmoidal decline of homeostatic component in subjective alertness and cognitive throughput. Sleep 1999, 22(Suppl):S94–S95.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barger, L.K., Lockley, S.W., Rajaratnam, S.M.W. et al. Neurobehavioral, health, and safety consequences associated with shift work in safety-sensitive professions. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 9, 155–164 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-009-0024-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-009-0024-7