Abstract

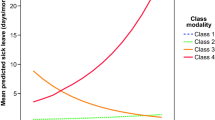

Little is known about the sick-leave experiences of workers who make a workers’ compensation claim for back pain. Our objective is to describe the 1-year patterns of sick-leave and the health outcomes of a cohort of workers who make a workers’ compensation claim for back pain. We studied a cohort of 1,831 workers from five large US firms who made incident workers’ compensation claims for back pain between January 1, 1999 and June 30, 2002. Injured workers were interviewed 1 month (n = 1,321), 6 months (n = 810) and 1 year (n = 462) following the onset of their pain. We described the course of back pain using four patterns of sick-leave: (1) no sick-leave, (2) returned to worked and stayed, (3) multiple episodes of sick-leave and (4) not yet returned to work. We described the health outcomes as back and/or leg pain intensity, functional limitations and health-related quality of life. We analyzed data from participants who completed all follow-up interviews (n = 457) to compute the probabilities of transition between patterns of sick-leave. A significant proportion of workers experienced multiple episodes of sick-leave (30.2%; 95% CI 25.0–35.1) during the 1-year follow-up. The proportion of workers who did not report sick-leave declined from 42.4% (95% CI 39.0–46.1) at 1 month to 33.6% (28.0–38.7) at 1 year. One year after the injury, 2.9% (1.6–4.9) of workers had not yet returned to work. Workers who did not report sick-leave and those who returned and stayed at work reported better health outcomes than workers who experienced multiple episodes of sick-leave or workers who had not returned to work. Almost a third of workers with an incident episode of back pain experience recurrent spells of work absenteeism during the following year. Our data suggest that stable patterns of sick-leave are associated with better health.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abenhaim L, Suissa S, Rossignol M (1988) Risk of recurrence of occupational back pain over three year follow up. Br J Ind Med 45:829–833

Baldwin ML, Johnson WJ, Butler RJ (1996) The error of using returns-to-work to measure the outcomes of health care. Am J Ind Med 29:632–641

Beurskens AJ, de Vet HC, Koke AJ (1996) Responsiveness of functional status in low back pain: a comparison of different instruments. Pain 65:71–76

Butler RJ, Johnson WJ, Baldwin ML (1995) Managing work disability: why first return to work is not a measure of success. Ind Labor Relat Rev 48:452–468

Cassidy JD, Côté P, Carroll L, Kristman V (2005) The incidence and course of low back pain in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Spine 30:2817–2823

Coste J, Delecoeuillerie G, Cohen de Lara A, Le Parc JM, JB Paolaggi JB (1994) Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: an inception cohort study in primary care practice. BMJ 308:577–580

Côté P, Baldwin ML, Johnson WG (2005) Early patterns of care for occupational back pain. Spine 30:581–587

Croft P, Macfarlane GJ, Papageorgiou AC, Thomas E, Silman AJ (1998) Outcome of low back pain in general practice: a prospective study. BMJ 316:1356–1359

Deyo RA (1986) Comparative validity of the sickness impact profile and shorter-scales for functional assessment in low-back pain. Spine 11:951–954

Deyo RA, Centor RM (1986) Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: an analogy to diagnostic test performance. J Chronic Dis 39:897–906

Frank JW, Brooker AS, DeMaio SE, Kerr MS, Maetzel A, Shannon HS, et al (1996) Disability resulting from occupational low back pain. Part II. What do we know about secondary prevention? A review of the scientific evidence on prevention after disability begins. Spine 21:2918–2929

Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Manniche C (2003) Low back pain what is the long-term course? A review of studies of general patient populations. Eur Spine J 12:149–165

Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Engberg M, lauritzen T, Bruun NH, Manniche C (2003) The course of low back pain in a general population. Results from a 5-year prospective study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 26:213–219

Hsiegh CY, Phillips RB, Adams AH, et al (1992) Functional outcomes of low back pain: comparison of four treatment groups in a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 15:4–9

Johnson WG (2004) Back pain: acute injury or chronic disease. Worker’s Compens Policy Rev 4:9–18

Kopec JA, Esdaile JM, Abrahamowics M, et al (1995) The Quebec back pain disability scale measurement properties. Spine 20:341–352

Kristman V, Manno M, Côté P (2004) Loss to follow-up in cohort studies: how much is too much? Eur J Epidemiol 19:751–760

Leclaire R, Bier F, Fortin L, et al (1997) A cross-sectional study comparing the Oswestry and Roland-Morris functional disability scales in two populations of patients with low back pain of different levels of severity. Spine 22:68–71

Little RJA, Rubin DB (1987) Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley, New York

Luo X, George ML, Kabouras I, et al (2003) Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the short form 12-item survey (SF-12) in patients with back pain. Spine 28:1739–1745

Picavet HSJ, Schouten JSAG (2003) Musculoskeletal pain in the Netherlands: prevalence, consequences and risk groups, the DMC3-study. Pain 102:167–178

Roland M, Morris R (1983) A study of the natural history of back pain—part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine 8:141–144

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70:41–55

Rossignol M, Suissa S, Abenhaim L (1988) Working disability due to occupational back pain: three-year follow-up of 2,300 compensated workers in Quebec. J Occup Med 30:502–505

SAS Institute (1990) SAS/STAT user s guide, version 6, vol 1 and 2. SAS Institute, Cary

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R (2003) Lost productive time and cost die to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA 290:2443–2454

Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, et al (1994) Assessing change over time in patients with low back pain. Phys Ther 74:528–533

Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, et al (1996) Defining the minimum level of detectable change for the Roland-Morris questionnaire. Phys Ther 76:359–368

Stratford PW, Finch E, Solomon B, et al (1996) Using the Roland-Morris questionnaire to make decisions about individual patients. Physiother Can 48:107–110

Troup JD, martin JW, Loyd DC (1981) Back pain in industry. A prospective study. Spine 6:61–69

van den Hoogen, Hans JM, Koes BW, van Eijk JTM, Bouter LM, Deville W (1998) On the course of low back pain in general practice: a one year follow up study. Ann Rheum Dis 57:13–19

Von Korff M, Barlow W, Cherkin D, Deyo RA (1994) Effects of practice style in managing back pain. Ann Intern Med 121:187–195

Waddell G, Aylward M, Sawney P (2002) Comparison of sickness and disability arrangements in various countries. Back pain, incapacity for work and social security benefits: an international literature review and analysis. Royal Society of Medicine Press Ltd, London, pp 73–100

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1995) SF-12. How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales, 1st edn. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34:220–233

Ware JE, Turner-Bowker DM, Kosinski M, et al (2002) SF-12v2™: how to score version 2 of the SF-12 health survey. QualityMetric Incorporated, Lincoln

Wasiak R, Pransky G, Webster B (2003) Methodological challenges in studying recurrence of low back pain. J Occup Rehabil 13:21–31

Wasiak R, Pransky G, Verma S, Webster B (2003) Recurrence of low back pain: definition-sensitivity analysis using administrative data. Spine 28:2283–2291

Williams DA, Feuerstein M, Durbin D, et al (1998) Health care and indemnity costs across the natural history of disability in occupational low back pain. Spine 23:2329–2336

Williams CT, Reno V, Burton JF (2004) Workers’ compensation: benefits, coverage, and costs, 2002. National Academy of Social Insurance, Washington

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant, with full freedom to publish, from the National Chiropractic Mutual Insurance Company (NCMIC), a national insurer of doctors of chiropractic. The authors thank the ASU Healthy Back Study Advisory Committee, composed of: Troyen A. Brennan, M.D., L.L.D.; Scott Haldeman, D.C., M.D., Ph.D.; Robert Mootz, D.C.; John J. Triano, D.C., Ph.D.; Margaret A. Turk, M.D.; Robert J. Weber, M.D. and Frank A. Zolli, D.C., Ed.D., for their guidance throughout the project. Finally, we thank Amy Bartels, Diana Fedesoff, Jane Irvine, Tricia Johnson, Rebecca White and Shap Wolf for their assistance with coordination and management of the study. The study would not have been possible without the cooperation and dedication of the participating employers and their employees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Côté, P., Baldwin, M.L., Johnson, W.G. et al. Patterns of sick-leave and health outcomes in injured workers with back pain. Eur Spine J 17, 484–493 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-007-0577-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-007-0577-6